Translated by Chae-Pyong Song and Anne Rashid

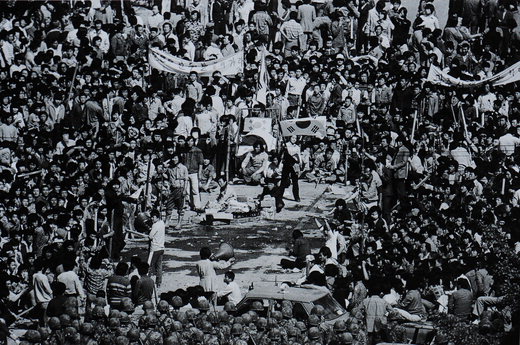

Mudeung Mountain, Photography by Seo Young-seok

He was in the Dark Cloud by Ra Hee-duk

I couldn’t see him,

so I couldn’t see the burn on his chest either

From the eastern window, I see Mudeung far away,

his dark green eyes look slack yet serene

but afraid of looking into the crater of my memory,

I couldn’t come near him, not even once.

His eyes that witnessed such ghastly death:

how could they look so peaceful?

How could his wounded chest look so green?

But today he sat inside a dark cloud.

Though I couldn’t see him,

I woke to the sound of breathing nearby.

When I returned every night to the village tucked under his arm

and slept like a wounded animal,

he would walk down step by step

and watch over my giddy sleepy head.

I have seen him many times, yet it’s as if I didn’t see him.

As the dark cloud lifted,

I saw his back walking up.

Mudeung slowly, who returned to Mudeung–

though I couldn’t see his burn mark in the green,

my hand was stained by his wound.

I woke up tucked under his arm.

그는 먹구름속에 들어 계셨다 / 나희덕

그가 보이지 않으니

가슴의 火傷 또한 보이지 않았다

동쪽 창으로 멀리 보이는 無等,

갈매빛 눈매는 성글고 그윽하였으나

그 기억의 분화구를 들여다보기가 두려워

한 번도 가까이 가지 못했다

너무도 큰 죽음을 보아버린 눈동자가

저리도 평화로울 수가 있다니,

진물 흐르는 가슴이 저리도 푸르다니,

그러나 오늘은 그가 먹구름 속에 들어 계셨다

그가 보이지 않았지만

아주 가까이 숨소리에 잠이 깨었다

밤마다 그의 겨드랑이께 숨은 마을로 돌아와

상처입은 짐승처럼 잠이 들면

그는 조금씩 걸어 내려와

어지러운 내 잠머리를 지키다 가곤 했으니

그를 보지 않은 듯 나는 너무 많이 보아온 것이다

먹구름이 걷히자

천천히 걸어 올라가는 그의 등이 보였다

無等에게로 돌아가는 無等,

녹음 속의 화상은 보이지 않았지만

내 손에는 거기서 흘러내린 진물이 묻어 있었다

그의 겨드랑이께에서 깨어났다

(Originally published in the Gwangju News, April 2012)

Ra Hee-duk (나희덕) was born in 1966 in Nonsan, Chungcheongnam-do. She received her Ph.D. in Korean literature from Yonsei University in 2006. She has published six books of poetry: To the Root (1991), The Word Dyed the Leaves (1994), The Place is Not Far (1997), That It Gets Dark (2001), A Disappeared Palm (2004), and Wild Apples (2009). She also published one collection of essays, A Half-filled Water Bucket (1999), and a volume of literary criticism, Where Does Purple Come From? (2003). Among her many literary awards are the Kim Suyoung Literature Award (1998), Modern Literature Award (2003) and the Sowol Poetry Award (2007). Growing up in orphanages, because her father was an administrator at an orphanage, she developed her strong sympathy for the less fortunate others. She currently teaches creative writing at Chosun University in Gwangju.

Kim Yong-taek (1948- ) was born in Imsil, Jeollabuk-do. With lyrical (often regional) vernacular, he has written many poems about undamaged agricultural communities and the profound beauty of nature. His poetry collections include The Sumjin River, A Clear Day, Sister, The Day Is Getting Dark, The Flower Letter I Miss, Times Like A River, That Woman’s House, and Your Daring Love. He also published essay collections such as A Small Village,What’s Longed for Exists behind the Mountain, A Story of the Sumjin River, and Follow the Sumjin River and Watch. He was awarded the Kim Soo-young Literary Award (1986) and the Sowol Poetry Award (1997). He currently teaches at Woonam Elementary School.

Kim Yong-taek (1948- ) was born in Imsil, Jeollabuk-do. With lyrical (often regional) vernacular, he has written many poems about undamaged agricultural communities and the profound beauty of nature. His poetry collections include The Sumjin River, A Clear Day, Sister, The Day Is Getting Dark, The Flower Letter I Miss, Times Like A River, That Woman’s House, and Your Daring Love. He also published essay collections such as A Small Village,What’s Longed for Exists behind the Mountain, A Story of the Sumjin River, and Follow the Sumjin River and Watch. He was awarded the Kim Soo-young Literary Award (1986) and the Sowol Poetry Award (1997). He currently teaches at Woonam Elementary School.