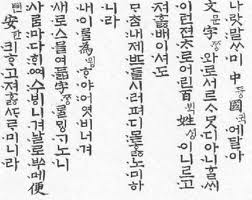

Translated by Chae-Pyong Song and Anne Rashid

Underneath the Rust Tree, Part Two by Jung Kut-byol

(녹나무 아래 2)

Love that comes like a picnic

in the place of excrement with blowflies,

enjoy

the remaining spring.

You, with the ruddy face, don’t reject me.

Hallucinated ears and hallucinated eyes

close up when rain patters in

the exiled wound—

I, dark like smoke.

The universe and I

will fall like flowers,

just boards walking, standing without nails hammered in.

(Originally published in WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, Volume 39, Numbers 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 2011)

Jung Kut-byol is a professor of Korean literature at Myungji University in Seoul, South Korea. Since 1988, she has worked as both a poet and a critic. She has published four poetry collections, My Life: A Birch Tree (1996), A White Book (2000), An Old Man’s Vitality (2005), and Suddenly (2008) and two collections of critical essays, The Poetics of Parody (1997) and The Language of Poetry Has a Thousand Tongues (2008). She has also edited an anthology titled In Anyone’s Heart, Wouldn’t a Poem Bloom? 100 Favorite Poems Recommended by 100 Korean Poets (2008).

Jung Kut-byol is a professor of Korean literature at Myungji University in Seoul, South Korea. Since 1988, she has worked as both a poet and a critic. She has published four poetry collections, My Life: A Birch Tree (1996), A White Book (2000), An Old Man’s Vitality (2005), and Suddenly (2008) and two collections of critical essays, The Poetics of Parody (1997) and The Language of Poetry Has a Thousand Tongues (2008). She has also edited an anthology titled In Anyone’s Heart, Wouldn’t a Poem Bloom? 100 Favorite Poems Recommended by 100 Korean Poets (2008).